Judaism: A System of Division Facilitated by Shibboleths, In-Group Preferences, and the Birth of Islam as a Response

The entire religion of Islam can be understood, in part, as a response to this exclusion. While Judaism isolated Isaac as the sole recipient of the covenant, Islam emerged to challenge this notion, asserting that the descendants of Ishmael were also part of God's promise.

A shibboleth is a linguistic or cultural marker used to identify members of a specific group, distinguishing them from outsiders. The term originates from the Bible, specifically in the Book of Judges (Judges 12:5-6), where the Gileadites used the word "shibboleth" to identify Ephraimites who could not pronounce it correctly. Those who failed this linguistic test were identified as outsiders and were killed. This biblical account serves as an early example of how specific markers were used to enforce division and maintain the integrity of a group, a concept that has been deeply embedded in Jewish tradition and practice throughout history.

The Covenant and the Origins of Division

Judaism, from its very inception, can be seen as a religion built on division. The foundation of this division is the covenant between God and Abraham, described in the Torah. This covenant, which promised Abraham that his descendants would inherit the land of Canaan and become a great nation, was initially broad in scope, meant to include all of Abraham’s descendants. However, through the intervention of Sarah, who insisted that Isaac alone should be the inheritor of God's promise, a significant division was created within Abraham’s family, one that would have profound implications for the development of Judaism and Islam.

In Genesis 21:10-12, Sarah demands that Abraham cast out Hagar and Ishmael to ensure that Isaac would be the sole inheritor of the covenant. This decision not only created a rift within Abraham's family but also set the stage for the division between the descendants of Isaac and Ishmael, eventually leading to the emergence of Judaism and Islam as distinct religious identities. The exclusion of Ishmael and his descendants from the covenant sowed the seeds of division, with Judaism evolving as a religion that emphasized separation and exclusivity.

Islam: A Response to Exclusion

The entire religion of Islam can be understood, in part, as a response to this exclusion. While Judaism isolated Isaac as the sole recipient of the covenant, Islam emerged to challenge this notion, asserting that the descendants of Ishmael were also part of God's promise. Islam presents itself as a religion of inclusivity, claiming that all of Abraham's descendants are included in the covenant and that they are rightful inheritors of God's blessing.

Islamic teachings emphasize that both Isaac and Ishmael were blessed by God, and Muslims believe that they, too, are part of the Abrahamic tradition. This inclusivity is demonstrated in the way that Islamic empires, particularly the Ottoman Empire, treated religious minorities. Unlike the divisive tendencies in Judaism, Islamic rulers often showed respect for the religious practices of Christians and Jews within their territories. For instance, the Ottomans allowed the Greek Orthodox Church to maintain its head in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), which stands to this day in the heart of an Islamic territory. Similarly, synagogues and churches were allowed to function within Muslim lands, illustrating the broader inclusivity that Islam espoused in contrast to the divisive nature of Judaism.

Shibboleths and In-Group Preference in Judaism

The use of shibboleths in Jewish tradition goes beyond the biblical story in Judges. Throughout history, various markers—linguistic, physical, and cultural—have been employed to distinguish Jews from non-Jews. These markers are not just identifiers; they are tools that enforce division and strengthen in-group cohesion.

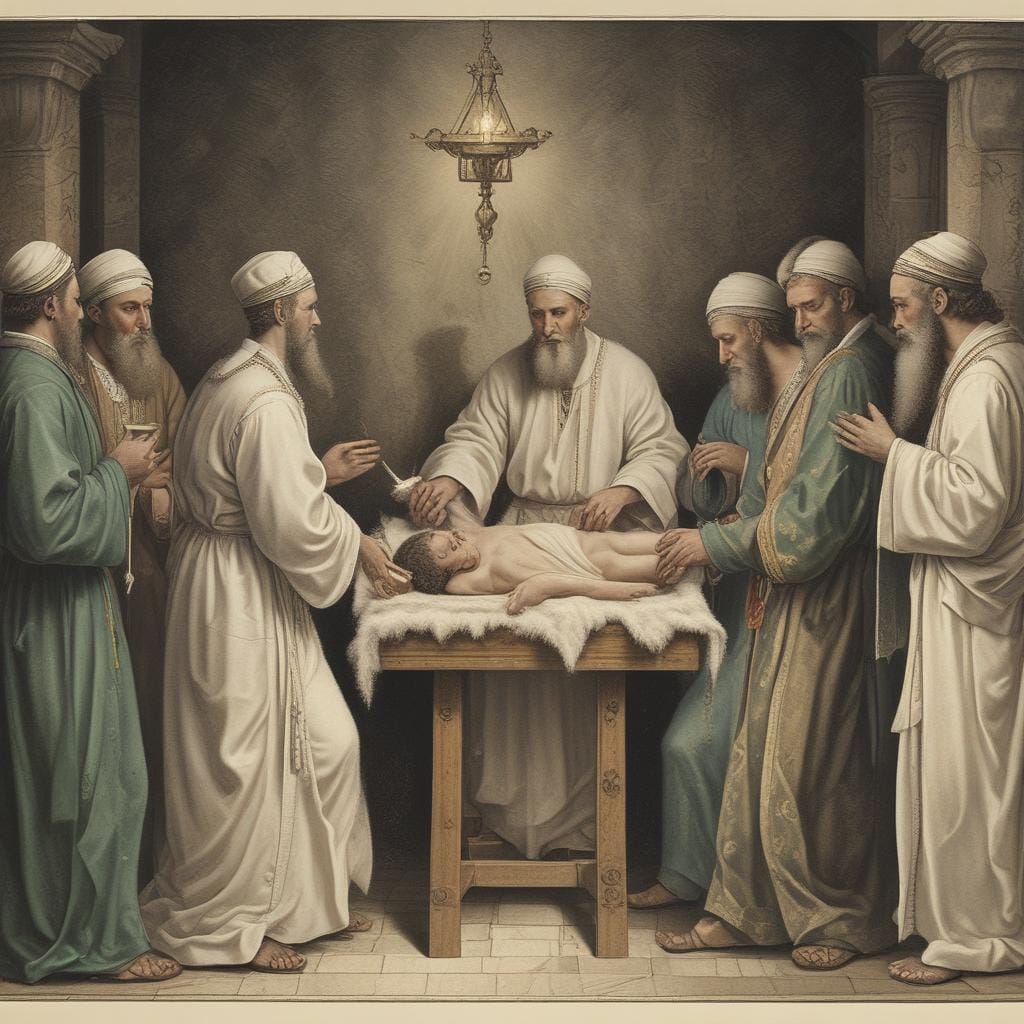

One of the most significant shibboleths in Judaism is circumcision (Brit Milah), as commanded in Genesis 17. While circumcision serves as a sign of the covenant between God and the Jewish people, it also functions as a physical marker that distinguishes Jewish males from non-Jews. But the practical implications of circumcision raise important questions: what is its purpose as a private marker? Who would be the one to see a circumcised penis? The answer lies in the intimate relationships within the community. A spouse or potential spouse would use circumcision as final verification that the person is truly Jewish before deciding to marry and have children with them, ensuring the continuation of the Jewish lineage. This practice underscores the in-group preference that is central to Jewish tradition, reinforcing the idea that Jewish identity and heritage must be preserved within the community.

Marriage practices within Jewish communities further illustrate this in-group preference. Historically, Jews have often practiced endogamy, or marrying within the group, including marrying close relatives such as first cousins. This practice was not just a cultural preference but a deliberate strategy to maintain the purity of the Jewish bloodline and to keep wealth and property within the family. By marrying within the family, Jewish communities were able to consolidate wealth and power, ensuring that both economic resources and religious identity were preserved.

Rabbinic teachings reinforce these practices by emphasizing the importance of supporting fellow Jews in both social and economic contexts. For example, Jewish law prohibits charging interest on loans to fellow Jews but permits it when dealing with non-Jews (Deuteronomy 23:19-20; Bava Metzia 71a). This practice, known as "heter iska," allowed wealth to circulate within the Jewish community, fostering economic solidarity and growth. By prioritizing in-group transactions, Jewish communities have historically been able to build and maintain strong economic foundations, further reinforcing the divisions that lie at the heart of Judaism.

Conclusion

Judaism is more than just a religion that creates division; it is a system fundamentally built on the concept of division. From the very beginning, through the covenant and the exclusion of Ishmael, Judaism has emphasized separation—between Jews and non-Jews, between sacred and profane, and between in-group and out-group. The use of shibboleths, whether in the form of linguistic tests, physical markers like circumcision, or cultural practices, serves to maintain and reinforce these divisions. In-group preference, as guided by Torah and rabbinic teachings, further solidifies these divisions by fostering economic and social cohesion within the Jewish community.

In contrast, Islam emerged as a response to this exclusion, promoting inclusivity and asserting the rights of all of Abraham’s descendants to God's covenant. Islamic history demonstrates a broader approach to inclusivity, as seen in the respect for religious minorities within Muslim lands and the coexistence of churches and synagogues under Islamic rule.

Understanding Judaism as a system of division highlights how these divisions have contributed to the survival and prosperity of the Jewish people throughout history. Through a combination of shibboleths, in-group preferences, and strategic marriage practices, Judaism has maintained its distinct identity while ensuring the preservation of wealth, power, and influence within the community.

References

- The Holy Scriptures: Torah, Prophets, Writings (Tanakh)

- The Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Bava Metzia 71a

- Maimonides, Mishneh Torah

- Genesis 17, Genesis 21:10-12, Deuteronomy 23:19-20, Judges 12:5-6

- Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam (Princeton University Press, 1984)

- Karen Armstrong, Islam: A Short History (Modern Library, 2002)